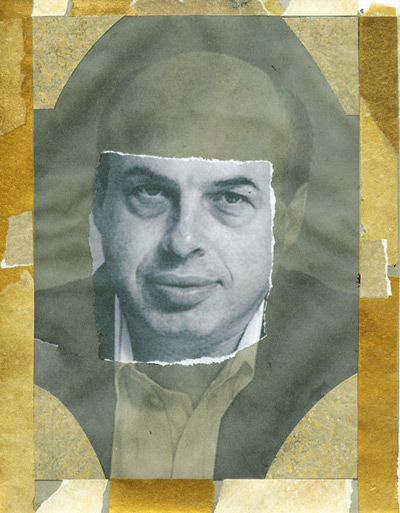

Natan Sharansky was born in the Ukraine in 1948. A math prodigy, he was admitted to the prestigious Moscow Physical Technical Institute, despite an enforced quota against Soviet Jews, where he studied mathematics and computer science. At the age of 25, he began his career as a computer scientist at the state-run Oil and Gas Research Institute.

The start of Sharansky’s professional career coincided with a growing sense of Jewish identity and an identification with the State of Israel, a phenomenon among many young Soviet Jews. In 1974, Sharansky, whose family had maintained their Jewish heritage despite efforts to suppress Judaism by Soviet authorities, decided to emigrate to Israel along with his future wife, Natalia Stieglitz.

Natalia’s request for a visa was approved, but Sharansky was denied permission to leave. The Soviet government insisted that he knew too many state secrets from his work at the Oil and Gas Research Institute. On the day before she left for Israel, Natalia married Anatoly. He promised that he would soon join her.

In 1975, the Soviet Union was one of the signers of the Helsinki accords, a set of conditions that not only guaranteed the current borders of all the states of Europe, a condition favorable to the Soviets, but also committed all the signatory nations to “respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief.” This was a clause that the Soviet Union had no intention of honoring.

But the Helsinki Accords allowed a small but influential group of Soviet human rights activists to monitor the article dealing with human rights and freedoms. In 1976, eleven of the activists founded the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group. Among the founders were the Soviet physicist ,“father of the Russian atomic bomb,” and political dissident Andrei Sakharov and a 28-year-old computer programmer named Anatoly Sharansky. Because he was fluent in English, Sharansky soon became the spokesperson for the group. He also became a prime participant in the Refusenik movement, the unofficial term for individuals, typically but not exclusively Soviet Jews, who were denied permission to emigrate abroad. The term refusenik was derived from the "refusal" handed down to a prospective emigrant from the Soviet authorities.

Within two years, Sharansky was declared an enemy of the State and arrested on charges of spying for the United States and for treason. On the day of his sentencing to thirteen years of forced labor in Perm 35, a Siberian Labor camp, he addressed his wife and the Jewish people:

For more than two thousand years the Jewish people, my people, have been dispersed. But wherever they are, wherever Jews are found, every year they have repeated, ‘Next year in Jerusalem.’ Now, when I am further than ever from my people, from Avital [his wife’s Hebrew name] facing many arduous years of imprisonment, I say, turning to my people, my Avital, ‘Next year in Jerusalem.’ Now I turn to you, the court, who were required to confirm a predetermined sentence: To you I have nothing to say.

Sharansky spent the next decade as a prisoner of the Soviet Union under terrible conditions, both in a Moscow prison and in the Siberian gulag, often in solitary confinement and in a special “torture cell.” He survived because of his religious belief, his resistance to despair and emotional surrender, and the promise he made to his wife about their eventual reunion in Israel. During those years, he became a symbol for human rights in general and Soviet Jewry in particular.

Finally, after an international campaign led by his wife to free him, Anatoly Sharansky was released from the gulag as part of an East-West prisoner exchange on a bridge between East and West Germany. He was met by the Israeli ambassador to West Germany who presented him with his new Israeli passport under the name Natan Sharansky.

In the more than two decades that Natan Sharansky has lived in Israel, he has achieved an extraordinary career as a journalist, Soviet Jewish activist, and Israeli government minister. In 1986, the United States Congress granted him the Congressional Gold Medal and in 2006, President George W. Bush awarded Sharansky the Presidential Medal of Freedom.