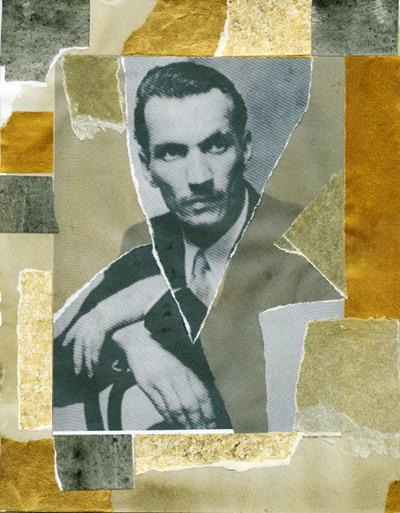

As a Polish Catholic, Jan Karski, 1914-2000, entered the forbidden world of the Warsaw Ghetto in late August 1942, months after Nazi Germany implemented its plans for the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question,” and saw streets and tenements filled with hungry and dying Jews. He witnessed what he later described as “terrible things.”

As a member of the Polish underground resistance to Nazi occupation, Karski breached the barbed wire gates of the Izbica Ghetto, a Jewish ghetto located near the city of Lublin and a collection point for Polish Jews and other Jews from Czechoslovakia, Germany, and Austria before they were shipped to the death camps of Belzec and Treblinka. He witnessed the murder of dozens of Jews being resettled from local ghettos to Izbica at the hands of brutal Ukrainian guards. Karski (born Jan Kozielewski in Poland’s second largest city, Lodz) was able to see both ghettos, because he was accompanied by members of the Jewish underground who wanted him to see for himself the ongoing destruction of Polish Jewry.

Why he chose to put his life in danger is a complex question. It may have had something to do with Karski’s childhood in a strict Roman Catholic home where religion and acceptance of Jews were important. His mother, a devout Catholic, also adored Marshal Jozef Pilsudski, the benign dictator who ruled Poland during the interwar years and who provided a relatively safe environment for its Jewish community.

But more than anything else, Jan Karski was a Polish patriot who embodied the finest ideals of the nation and the human being. A skilled courier, he was ordered to travel to the nations of the free world to inform them of the plight of Poland and, only incidentally, the plight of its Jewish community.

In November 1942, Karski reached London, the seat of the Polish government-in-exile. After delivering microfilm documents to Polish officials, he scheduled a meeting with the British foreign secretary, Anthony Eden. After telling Eden what he had seen in Warsaw and Izbica, Karski was told by Eden that Great Britain could do no more; it had already done enough by accepting 100,000 refugees.

Karski arrived in Washington in July 1943. He was aware that a few months earlier, in April, the heroic remnants of the Warsaw Ghetto had resisted the Nazi attempt to liquidate those Jews not yet shipped to death camps. For three weeks, before the Uprising was crushed, the Ghetto’s Jews had put up a heroic if impossible struggle. The remaining 56,000 Warsaw Ghetto Jews were taken to the Treblinka death camp.

He arranged a secret meeting with Franklin Delano Roosevelt in which he told the American president that if the Allies did not intervene during the next eighteen months the Jews of Poland would “cease to exist.” Roosevelt replied that Karski was to tell the Polish government “it has a friend in the White House,” but said nothing about the plight of the Jews.

Prior to his meeting with Roosevelt, Karski also met with Felix Frankfurter, a Jewish justice of the American Supreme Court. “Will you tell me about the Jews,” Frankfurter asked. “We have had many reports. What happens to the Jews in your country?”

When Karski reported on what he had seen in the Polish ghettos, Frankfurter rose from his chair and turned away deep in thought. When he faced Karski again, Frankfurter said: “Young man, I am no longer young. Men like me and you must be totally honest. And I am telling you: I do not believe you…. My mind and my heart are made in such a way that I cannot accept it. No! No! No! I am a judge of men. I know humanity. I know men. It is impossible.”

“Almost every individual was sympathetic to my reports concerning the Jews,” Karski later wrote. “But when I reported to the leaders of governments, they discarded their conscience, their personal feeling.”

Jan Karski remained in the United States as a professor at Georgetown University. He did not seek glory or recognition for his efforts. He lived, rather, with the realization that the world did not care enough about the murder of Poland’s and Europe’s Jews to act in any meaningful way despite evidence of what was taking place.

But world Jewry did care about what Jan Karski had done, even in failure. In 1982 he was recognized by Yad Vashem as a Righteous Among the Nations. In 1994, Professor Karski was awarded honorary citizenship of Israel. At the ceremony he stated: “This is the proudest and most meaningful day in my life. Through the honorary citizenship of the State of Israel, I have reached the spiritual source of my Christian faith. In a way, I also became a part of the Jewish community… And now I, Jan Karski, by birth Jan Kozielewski—a Pole, an American, a Catholic—have also become an Israeli.”