Jews were not the only people imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps: there were also Polish, Roma/Gypsies, homosexuals, communists, and black people. There were about 20-25,000 blacks in Germany at the time of the Third Reich out of a population of 60 million.

German antagonism toward blacks dates back to the 1800s, when Germany had African colonies. By 1890, some colonial officials refused to register interracial marriages, arguing that interracial children were inferior, and this became policy throughout most German colonies by 1912. The German parliament debated the policy, concerned that these colonial interracial children would have German citizenship and could return to Germany, vote, serve in the military, and hold public office.

Under the Third Reich, blacks were socially isolated and forbidden to have sex with or to marry Aryans. They experienced discrimination in employment, welfare, and housing, and were were not allowed to pursue higher education. They were at the bottom of the racial scale of non-Aryans, along with Jews and Roma people.

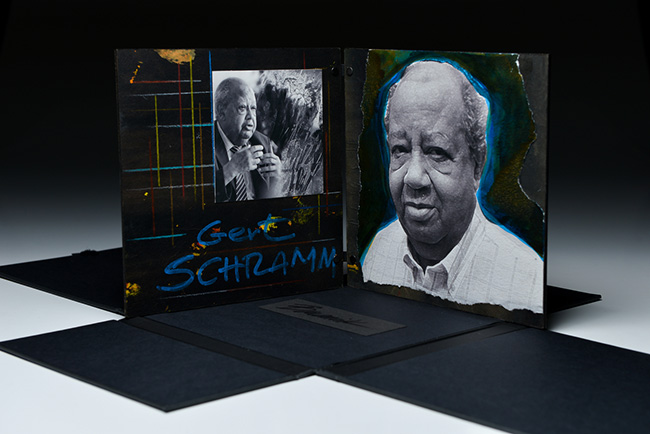

This was what Germany was becoming when Gert Schramm was born to Marianne Schramm, a German woman, and Jack Brankson, a black American engineer from an American steel company who was in Germany working on a contract to build a bridge.

Brankson needed a new suit and went to the shop of tailor Kurt Schramm, where he met Marianne, the owner’s daughter. They fell in love, married, and in late 1928, their son Gert was born. Even after his contract ended, Brankson kept returning to Germany to see Marianne and Gert, both living with her parents.

After finishing his compulsory education, Gert worked as a helper in a car repair shop. According to the Nuremberg Laws, he was denied the right to vocational training because he was a “mixed race of the first grade.” He was also living proof of illegal interracial "incest" that carried the death penalty for himself and his father.

Brankson returned to Germany in 1941 to rescue his wife and child but was arrested for violating Nazi racial laws. He was deported to Auschwitz, where he apparently died.

Gert was arrested in May 1944, when he was 15 years old. He was moved from one Gestapo prison to another, held in "protective custody," interrogated, denied food and drink, and hit in the face. In July 1944, he was deported to Buchenwald. He was the the youngest prisoner and also the only black person there. Other prisoners included Jews, communists. social democrats, priests and homosexuals, and Russian prisoners of war.

Gert was sent to the camp’s section for political prisoners and went to work in a stone quarry. The survival rate of prisoners working there was very low – 10 to 15 men were carried out dead on a daily basis. Many died of exhaustion or were shot “on the run.“ In the barracks, up to five men shared a bed.

Willy Bleicher, a communist and unionist responsible for collecting statistical data on the inmates for the SS, managed to have Gert “transferred“ from the stone pit to a food counter, until he got back his strength.

“I was lucky that I was put in with the political prisoners. The communists saved my life since I would not have survived the stone pit,“ he later said.

During the daily roll call, the smallest offense was punished by death. Whoever stood out or broke the ranks would not survive. As the only black among 70,000 prisoners, Gert’s fellow prisoners helped him to hide in plain sight. Otto Grosse, the oldest inmate in his block, managed to have Gert surrounded by the other prisoners during the daily roll call. They knew that if he were in the front lines at roll call he would not last very long.

In an interview for a book by Mark Jacobson, Gert said that he saw some black soldiers at the camp after liberation. “This was incredible to me. Outside of my father, who had been missing for so long, I’d never seen a black person until the Americans came. I knew these people looked like me but I never thought of myself as black. I was a German and this was how I looked. This was what I saw in the mirror, myself, that was all. So I was amazed to see the black soldiers.”

In June 1945, Gert Schramm returned home, on foot. He worked at a uranium mine in the Soviet occupation zone. From 1956 to 1964, he worked in a coal mine, and then moved to East Germany, three years after the construction of the Berlin Wall. There, he worked at a bus company, and resumed his education, becoming a certified mechanic and later, a master mechanic, and moved up the ranks before moving to a civil engineering combine.

With the help of another former Buchenwald prisoner, Hermann Axen, who had been among the group of Communist prisoners who protected Schramm, he started his own business in 1985, "Schramms Reisen," a taxi company now run by his son.

Gert Schramm is a father of four, grandfather and great-grandfather, and a widower. For years, he has been visiting schools to talk about Buchenwald and to warn about the recent neo-Nazi movement. He is still on the prisoners’ advisory board of the Buchenwald Memorial foundation.

He is convinced that evil needs to be confronted early. He has made it his life‘s mission.

Technical Information

Panels are 8"x8" archival textured gesso board bound with black leather straps; mixed-media acrylic ink, paint, and modeling paste. Custom presentation and storage flaps included.