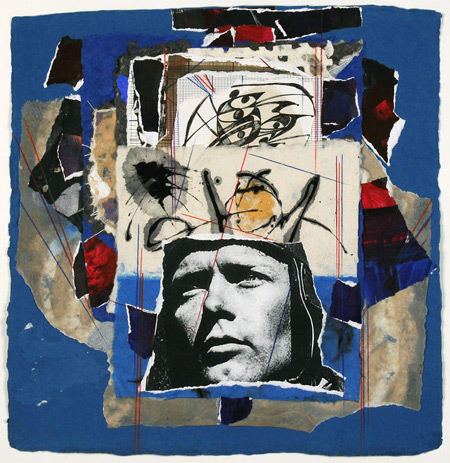

Charles A. Lindbergh would achieve greatness and fame as the first man to fly nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean in May 1927 in his single-seat, single-engine airplane called “The Spirit of St. Louis.” For this astonishing feat, he received America’s highest honor, the Medal of Freedom. The decades following this historic accomplishment, however, would bring him sorrow, shame, and infamy. His racist, anti-Semitic statements before, during, and after World War II, would disgrace his name and embarrass the country that once honored and revered him.

After Lindbergh’s famous flight from New York to Paris, he achieved great fame and status as an American hero. A postage stamp was issued in his honor; he was a sought-after speaker and spokesperson. Everyone wanted to meet him and to hear his opinions on the important events of the day.

In spite of his popularity, though, a great tragedy befell his family. In March of 1932, his infant son, Charles Jr., was kidnapped from his nursery in the Lindbergh’s New Jersey home. The child’s body was later discovered in the woods. A man named Bruno Hauptmann was caught, convicted, and put to death for the crime. The Lindberghs, fearing for the safety of their family, fled to Europe, where they lived until America entered World War II.

Before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Lindbergh was adamant about keeping America out of the European conflict. In an article he wrote for Reader’s Digest in 1939, he spoke of “that priceless possession, our European blood,” going on to write in his diary that Americans must “guard ourselves against attack by foreign armies and dilution by foreign races.” He testified before Congress advocating for a neutrality pact with Germany, saying that only three groups wanted America to enter the war: “the British, the Jewish and the Roosevelt administration.” His trips to Nazi Germany where he met with several Nazi top officials, his writings about Germany’s “Jewish problems,” his advocacy of limiting “to a reasonable amount the Jewish influence,” and his belief that the survival of the white race was more important than that of democracy, led President Franklin Roosevelt to tell his Secretary of the Treasury that he believed Lindbergh was a Nazi. Lindbergh’s supporters denied this characterization, saying that Lindbergh was merely politically naïve and inexperienced. Still, according to his great friend, Henry Ford, the automobile magnate, who hosted Lindbergh at his Detroit estate many times, “we only talk about the Jews.”

Because of Lindbergh’s anti-Jewish statements, he was denied a commission as an officer in World War II. He was able, however, to serve as a consultant to several aircraft companies for the duration of the war. His commission to the Army was restored by President Dwight Eisenhower who made him a Brigadier General in 1954. Lindbergh also served on a panel that established the United States Air Force Academy. His autobiography, The Spirit of St. Louis, won him a Pulitzer Prize.

Still, none of these accomplishments could wipe out his identity as an anti-Semite who blamed the Jews, among others, for America’s entrance into World War II. When Lindbergh died in 1974, it was amid scandal, for he had been discovered to have fathered a second family in France while still married to his wife, Anne. These facts, coupled with his anti-Semitic writings and speeches, overshadowed his reputation as a man of great achievement and accomplishment.